Inclusive Language in Exhibition Labels and Catalogs: How to Make Art Accessible to Everyone

Have you ever stood in front of a painting or sculpture, read the label beside it, and felt like the words were talking at you instead of to you? That’s not just a feeling-it’s a design flaw. Many exhibition labels and catalogs still use language that pushes people away instead of inviting them in. Outdated terms, passive voice, academic jargon, and unexamined biases turn visitors into spectators, not participants. Inclusive language isn’t about political correctness. It’s about clarity, respect, and making sure everyone-regardless of background, ability, or identity-can connect with the art.

Why Inclusive Language Matters in Museums

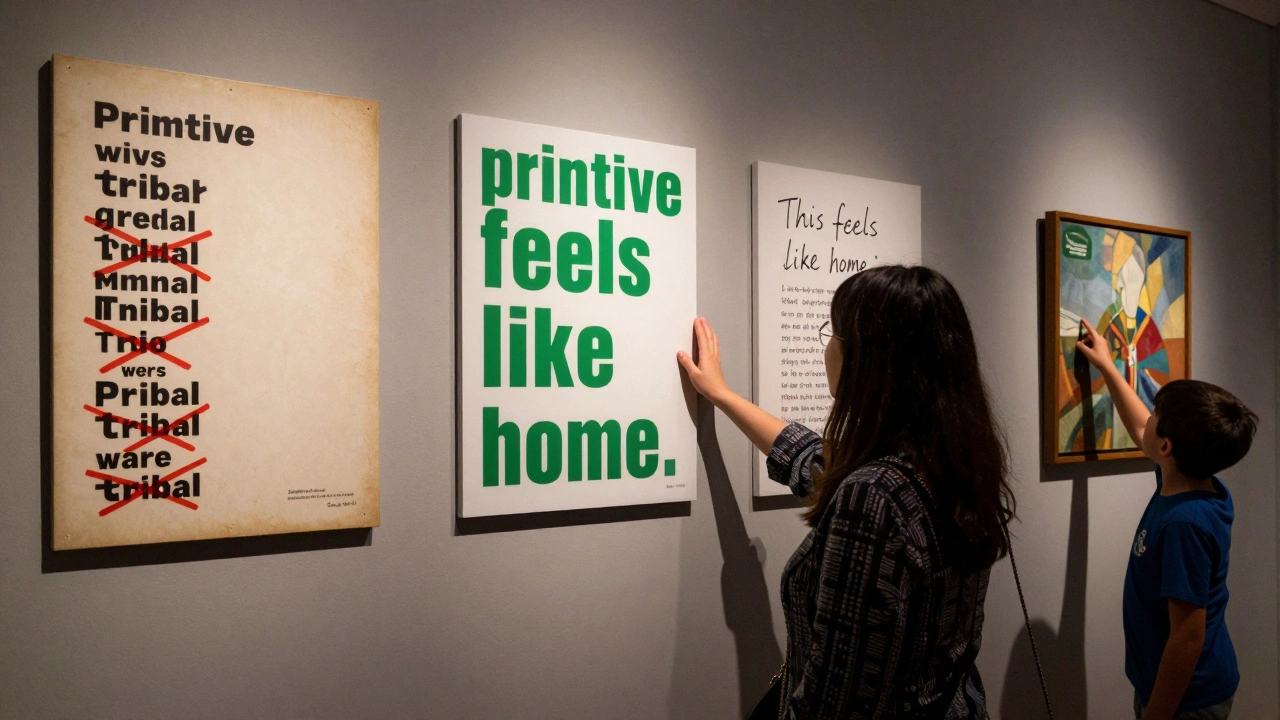

Museums aren’t just storage units for old objects. They’re spaces where stories are told. And stories shape how we see the world. When a label says "primitive African sculpture" instead of "sculpture from the Yoruba tradition," it doesn’t just misinform-it dehumanizes. Words like "primitive," "exotic," or "tribal" carry colonial baggage. They reduce cultures to stereotypes and erase agency. A 2023 study by the American Alliance of Museums found that 68% of visitors from underrepresented communities felt alienated by the language used in permanent galleries. That’s not a small number. That’s a system failing its audience.

Language also affects accessibility. If a label uses phrases like "the artist’s oeuvre" or "this piece exemplifies postmodern deconstruction," it assumes a level of education not everyone has. Art should be open to curiosity, not gated by terminology. A visitor with limited English, a high school student, or someone who learned art through lived experience-not academia-shouldn’t need a dictionary to understand what they’re seeing.

What Inclusive Language Looks Like

Good language doesn’t hide behind complexity. It’s clear, direct, and human. Here’s what works:

- Use active voice: Instead of "The painting was created by the artist in 1947," say "In 1947, the artist painted this scene."

- Name people and places: Instead of "Native American pottery," say "Pottery made by the Hopi people in northern Arizona."

- Avoid value judgments: Don’t call something "beautiful" or "strange." Describe it. "The ceramic vessel has raised geometric patterns and a matte black glaze."

- Use present tense for living artists: "She paints with bold brushstrokes" not "She painted with bold brushstrokes." It reminds us these are real people, not relics.

Consider this example:

Before: "This artifact represents the spiritual beliefs of a forgotten tribe."

After: "This ceremonial mask was used in dances by the Kwakwaka’wakw people of the Pacific Northwest. It honors ancestral spirits and is still used in ceremonies today."

The difference isn’t just in word count. It’s in dignity.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

Even well-meaning curators make mistakes. Here are the most common traps:

- Overgeneralizing cultures: "Asian art," "African art," or "Latin American art" aren’t categories. They’re continents with thousands of distinct traditions. Be specific: "Textiles from the Oaxaca region," "Woodcarvings from the Asante Kingdom."

- Using passive language to erase responsibility: "The collection was acquired in 1923" hides how it was obtained. If it was taken during colonization, say so. "The object was taken from a village in 1923 during colonial raids."

- Assuming gender: Don’t say "the artist’s wife" unless you know the relationship. Say "the artist’s partner" or "the person who modeled for this portrait."

- Ignoring non-Western perspectives: If a sculpture represents a deity in a non-Christian tradition, don’t call it "idolatry." Call it "a sacred representation."

Language that avoids these traps doesn’t just correct history-it builds trust.

How to Rewrite Labels and Catalogs

Changing language isn’t a one-time project. It’s an ongoing practice. Here’s how to start:

- Involve community voices. Don’t just hire a linguist. Work with cultural advisors from the communities represented. A Navajo elder, a contemporary Indigenous artist, or a descendant of the original makers can spot language that feels wrong long before a curator does.

- Test labels with real visitors. Put draft labels on display and ask people: "What does this tell you about the object?" If they’re confused, it’s not clear enough.

- Use plain language guidelines. Aim for an 8th-grade reading level. Tools like Hemingway Editor or the Flesch-Kincaid test help. But don’t rely on them alone-human judgment matters more.

- Update catalogs systematically. Don’t wait for a full exhibit overhaul. Start with one gallery. Rewrite ten labels. See how visitors respond. Then expand.

- Include multiple voices. A label doesn’t have to be one voice. Add a short quote from an artist, a curator, or a community member. "This piece reminds me of my grandmother’s kitchen," says Maria Lopez, whose family made similar bowls in Oaxaca."

At the Minneapolis Institute of Art, staff rewrote 120 labels over six months with input from 17 cultural advisors. Visitor feedback improved by 41%. Attendance from communities of color rose by 29% in the following year.

What About Catalogs?

Catalogs are where labels go to live forever. They’re often written in dense academic prose, filled with footnotes and citations that no one reads. But they’re also the main record of your exhibition. They’re used by researchers, students, and future curators.

Revise them the same way:

- Replace jargon with plain language.

- Define terms the first time they appear.

- Use inclusive pronouns and avoid gendered assumptions.

- Include diverse contributors-not just curators, but artists, historians, and community members.

- Offer multiple formats: PDF, audio, large print, and plain text versions.

A catalog from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art in 2025 included audio clips from artists explaining their work in their native languages. It became one of the most downloaded resources on their site.

The Bigger Picture

Inclusive language is one piece of a larger shift. Museums are no longer just temples of the elite. They’re public spaces. And public spaces should reflect the people who use them. Language is the first step. It’s the entry point. If the words don’t welcome you, you won’t stay. If they don’t honor you, you won’t return.

Art doesn’t need to be explained. It needs to be understood. And understanding begins with a single sentence-one that speaks clearly, honestly, and with respect.

What’s the difference between inclusive language and political correctness?

Inclusive language isn’t about avoiding offense for its own sake. It’s about accuracy and respect. "Political correctness" often sounds like censorship. Inclusive language is about replacing outdated, harmful, or vague terms with ones that reflect reality. Saying "Indigenous peoples" instead of "natives" isn’t about being trendy-it’s about recognizing sovereignty and identity. It’s not about policing words. It’s about choosing words that honor people.

Do I need to rewrite every label in my museum?

No. Start small. Pick one gallery, one exhibit, or one object that’s been problematic. Rewrite its label with input from community members. Test it. See how visitors react. Then expand. Change doesn’t happen overnight. But it starts with one clear sentence.

Can I use inclusive language without losing academic rigor?

Yes. Academic depth doesn’t require complex language. You can explain a 19th-century art movement using simple terms and still include references to key scholars. Use footnotes, appendices, or QR codes for deeper sources. The label should invite curiosity, not shut it down. Clarity and scholarship aren’t opposites-they’re partners.

What if a community disagrees on how to describe something?

That’s normal-and good. Different communities have different relationships to objects. Instead of choosing one "correct" version, offer multiple perspectives. A label might say: "Some community members refer to this as a ceremonial object. Others see it as a historical record. Here’s what both views tell us." This doesn’t confuse visitors. It shows that history isn’t fixed-it’s lived.

How do I know if my language is working?

Watch how people engage. Do they linger? Ask questions? Take photos? Talk to others? Ask for feedback directly: "Did the label help you understand the object?" Use anonymous surveys or comment cards. Look for patterns. If people of a certain background stop visiting after a label change, you may have missed something. Listen more than you correct.