How to Authenticate Photographs: Editions, Provenance, and Stamps Explained

When you hold an old photograph in your hands, you might wonder: is this real? Not just in the sense of being an actual print, but as a genuine piece of history - made by the artist, from the right time, and with a clear story behind it. Authenticating photographs isn’t just about spotting forgeries. It’s about understanding editions, tracing provenance, and decoding the small but critical details like stamps and signatures. Many collectors have lost money because they trusted appearance over evidence. Others have found hidden value in prints they thought were just family snapshots. The truth is, the difference between a worthless print and a museum-worthy original often comes down to three things: how many were made, where it’s been, and what marks it carries.

Understanding Editions: Limited vs. Unlimited

Not all photographs are created equal. In the art world, an edition is a set of identical prints made from the same negative or digital file, under the artist’s supervision. A limited edition means the artist decided in advance how many copies would ever be made - usually between 5 and 50 for fine art photographers like Ansel Adams or Diane Arbus. Once that number is printed, no more are allowed. This scarcity drives value.

Unlimited editions, on the other hand, are mass-produced. Think postcards, magazine reproductions, or prints sold at tourist shops. These have no collector value. The key is to find documentation. Reputable galleries and auction houses list the edition size on certificates of authenticity. If you’re looking at a print labeled "limited edition" but have no proof of how many were made, treat it with suspicion.

Some photographers, like Robert Frank, signed every print in their limited editions. Others, like Lee Friedlander, didn’t sign at all. That doesn’t mean it’s fake - it means you need to look elsewhere. Check the print quality. Originals from the 1930s to 1970s were often contact printed on fiber-based paper, which has a slightly textured surface and rich blacks. Modern inkjet prints on glossy paper? That’s likely a reproduction.

Provenance: The Paper Trail That Matters

Provenance is the recorded history of ownership. It’s not glamorous. It’s receipts, gallery labels, exhibition catalogs, old letters, and auction records. But without it, even the most beautiful photograph can be worthless.

Take a 1940s print by Edward Weston. If it came from the artist’s studio, then to a known collector in California, then to a museum in New York, and finally to you - that’s strong provenance. Each step adds credibility. If the seller says, "I found it in my grandfather’s attic," that’s not enough. But if you can trace it back to a 1957 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art with a catalog listing the piece, you’re on solid ground.

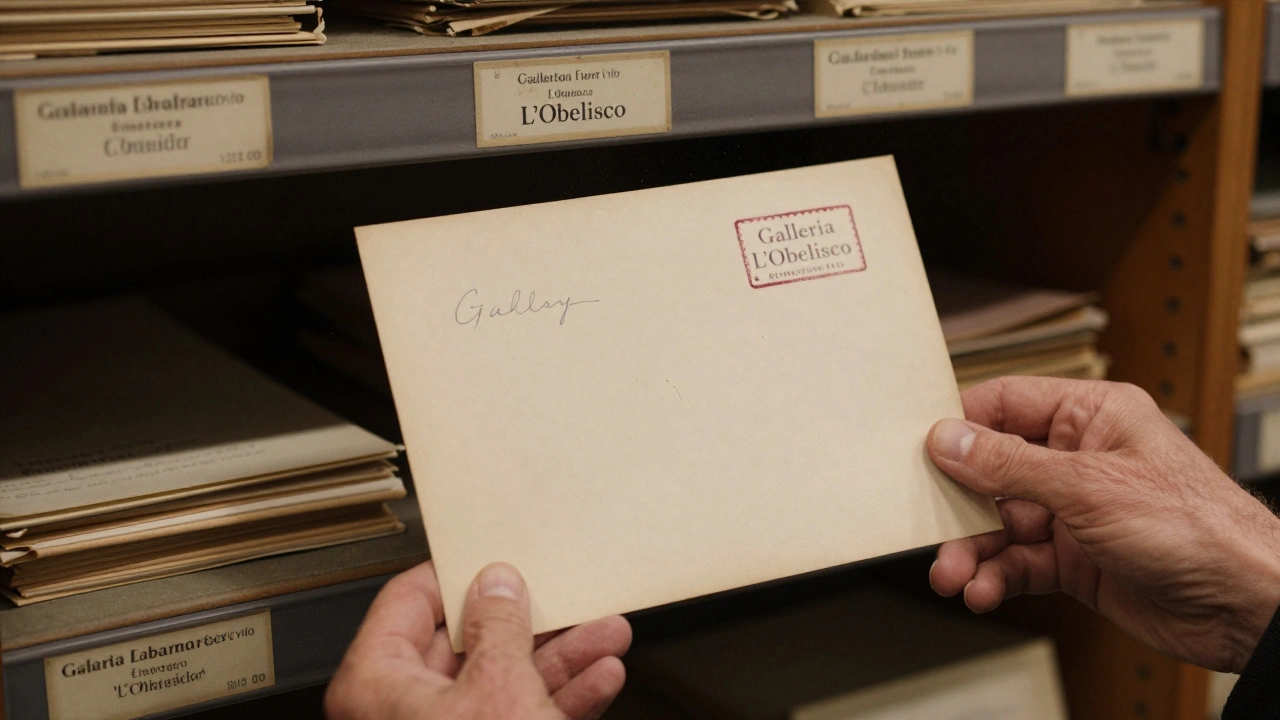

Provenance doesn’t have to be perfect. Sometimes, all you have is a faded gallery sticker on the back. But even that matters. A 1960s Galleria L’Obelisco stamp from Rome on a Henri Cartier-Bresson print is a powerful clue. These galleries didn’t just sell anything - they worked directly with artists. A sticker from a defunct gallery with known ties to the photographer? That’s gold.

Always ask: Has this photograph been in a public collection? Was it ever published? Has it been exhibited? If the answer is no, don’t panic - but don’t pay top dollar either. Provenance isn’t about bragging rights. It’s about reducing risk.

Stamps, Signatures, and Labels: The Small Details That Confirm Authenticity

Photographs often carry physical marks. These aren’t just decoration. They’re fingerprints of authenticity.

Artist signatures are the most obvious. But here’s the catch: many photographers didn’t sign every print. Some signed only the first few. Others signed on the back. Some used pencil, not ink. An ink signature on a 1920s gelatin silver print? That’s suspicious. Pencil was standard. Ink fades or smudges on older paper.

Stamps are even more telling. Galleries, museums, and dealers used ink stamps to track ownership. A stamp from the George Eastman House, the International Center of Photography, or a major auction house like Christie’s is a strong indicator. These institutions didn’t stamp random prints. They stamped items they had verified.

Look for:

- Artist’s stamp: Often a small, circular stamp with the photographer’s name and location (e.g., "Ansel Adams, Carmel, CA").

- Gallery stamp: Found on the back or lower corner. May include the gallery’s name, address, and date.

- Auction stamp: Usually a red or black ink stamp with the auction house name and lot number.

- Exhibition stamp: Sometimes includes the show title and year.

Be wary of fake stamps. Counterfeiters often copy them poorly. A real stamp has slight imperfections - ink smudges, uneven pressure, or fading. A too-perfect stamp? That’s a red flag.

Labels matter too. A handwritten label with the title, date, and edition number on the reverse, in the same handwriting as the artist’s known notes? That’s powerful. A printed sticker with generic text? Probably not.

Materials and Techniques: What the Print Tells You

The paper, the emulsion, the mounting - all of it tells a story.

From the 1880s to the 1960s, most fine art photographs were printed on fiber-based paper. This paper has a soft, slightly rough texture. It absorbs toners well, giving deep blacks and subtle grays. Modern prints use resin-coated (RC) paper - it’s smooth, plastic-like, and often has a glossy finish. If your 1940s print looks like it came out of a photo kiosk, it’s likely a copy.

Look at the edges. Originals from the 1930s-1950s were often trimmed by hand. The edges are slightly uneven. Machine-cut prints from later decades have perfectly straight edges. That’s not a flaw - it’s a clue.

Check for mat burn. Older prints were sometimes mounted directly to a backing without a mat. Over time, the acidic backing can leave a brownish stain around the image. That’s normal. If you see it, it’s a sign the print is old. If you don’t see it on a print claimed to be from 1920, you might be looking at a fake.

Ultraviolet light can reveal hidden details. Many modern reproductions use fluorescent whitening agents that glow under UV. Originals from before 1970 won’t. This isn’t a test you can do at home - but a reputable dealer will have a UV lamp on hand.

Common Pitfalls and Red Flags

Even experts get fooled. Here’s what to watch out for:

- "Original negative" claims: Just because someone says it’s printed from the original negative doesn’t mean it’s authentic. Many negatives were reused decades later.

- "Signed by the estate": Estate-signed prints are common, but they’re not the same as artist-signed. They’re usually marked "after the artist" and are worth far less.

- Too many copies: If a print claims to be from a limited edition of 20, but 50 exist, it’s not legitimate.

- No documentation: If the seller can’t provide a certificate, receipt, or history - walk away.

- Perfect condition: A 1930s photograph with no fading, no foxing, no creases? That’s rare. It might be a modern reproduction made to look old.

Also, beware of online marketplaces that list "vintage" prints with no provenance. Many sellers use stock images from museum websites and print them as "originals." If the photo is from a well-known collection, check the museum’s online archive. If it’s there, and yours doesn’t match the dimensions or markings, it’s a fake.

What to Do When You’re Not Sure

If you’ve got a photograph you think might be valuable - but you’re not certain - don’t guess. Go to a professional.

Libraries and archives often have photo conservation departments. The George Eastman Museum, the Getty Research Institute, and the Library of Congress offer free or low-cost evaluation services for researchers. University art departments with photography programs can also help.

For high-value pieces, consider hiring a certified photograph appraiser. Organizations like the International Society of Appraisers or the American Society of Appraisers list qualified experts. They’ll examine the print under magnification, check paper composition, and cross-reference stamps and signatures with known archives.

Don’t rush. Authenticating a photograph takes time. It’s not like grading a coin. It’s like reading a letter from the past - every detail matters.

Final Thought: Value Isn’t Just About Money

At its core, photograph authentication isn’t about making money. It’s about preserving history. A single print can carry the voice of a photographer, the moment they chose to press the shutter, and the hands that cared for it over decades. When you authenticate a photograph, you’re not just verifying its origin - you’re honoring its story.

So next time you come across an old photo - whether it’s in a dusty box or a gallery - ask: Who made this? How many were made? Where has it been? What marks does it carry? Those questions don’t just reveal value. They reveal truth.