Experimental Exhibition Formats: Performance and Participation in Modern Curating

What if the art wasn’t just on the wall-but in your movements, your voice, your hesitation? Over the last decade, museums and galleries have stopped asking visitors to just look. They’re asking them to do. And that shift is rewriting what an exhibition can be.

From Passive Viewing to Active Doing

Traditional galleries used to be quiet temples of observation. You walked in, read the plaque, stared at the painting, moved on. But today’s experimental exhibitions are built on the idea that meaning isn’t found in looking-it’s built through doing. This isn’t just about adding interactive screens or touch panels. It’s about inviting people into the creative act itself.Take The Living Room at the Hammer Museum in 2023. Visitors weren’t shown a recreated domestic space. They were given keys to a real apartment next door, asked to live there for 48 hours, and document their routines. The exhibition only existed as the photos, audio logs, and grocery receipts left behind. No curator chose what to display. The participants did.

This kind of work doesn’t just change how art is seen-it changes who gets to make it. Curators now act more like facilitators. Their job isn’t to select the best objects. It’s to design systems that let people become part of the artwork.

Performance as the Core, Not the Addition

Performance art used to be a side note in exhibitions-a live dance piece tucked into a corner, scheduled for one night only. Now, it’s often the whole point.At the 2025 Venice Biennale, a piece called Echo Chamber had no physical objects. Instead, 12 performers repeated phrases shouted by visitors throughout the day. Every utterance was recorded, filtered through AI, and whispered back in real time by actors dressed as museum guards. Visitors didn’t just watch-they triggered the performance. And the performance changed depending on who spoke, how loudly, and what they said.

These aren’t theatrical shows. They’re dynamic, unpredictable systems. One visitor might say, “I’m tired,” and the whole room hums with exhaustion. Another says, “I’m afraid,” and the performers freeze. The exhibition responds. It learns. It adapts.

And that’s the radical part: the artwork has no fixed form. It exists only in the moment of participation. You can’t photograph it. You can’t buy it. You can only remember it.

Participation Isn’t Just About Engagement-It’s About Ownership

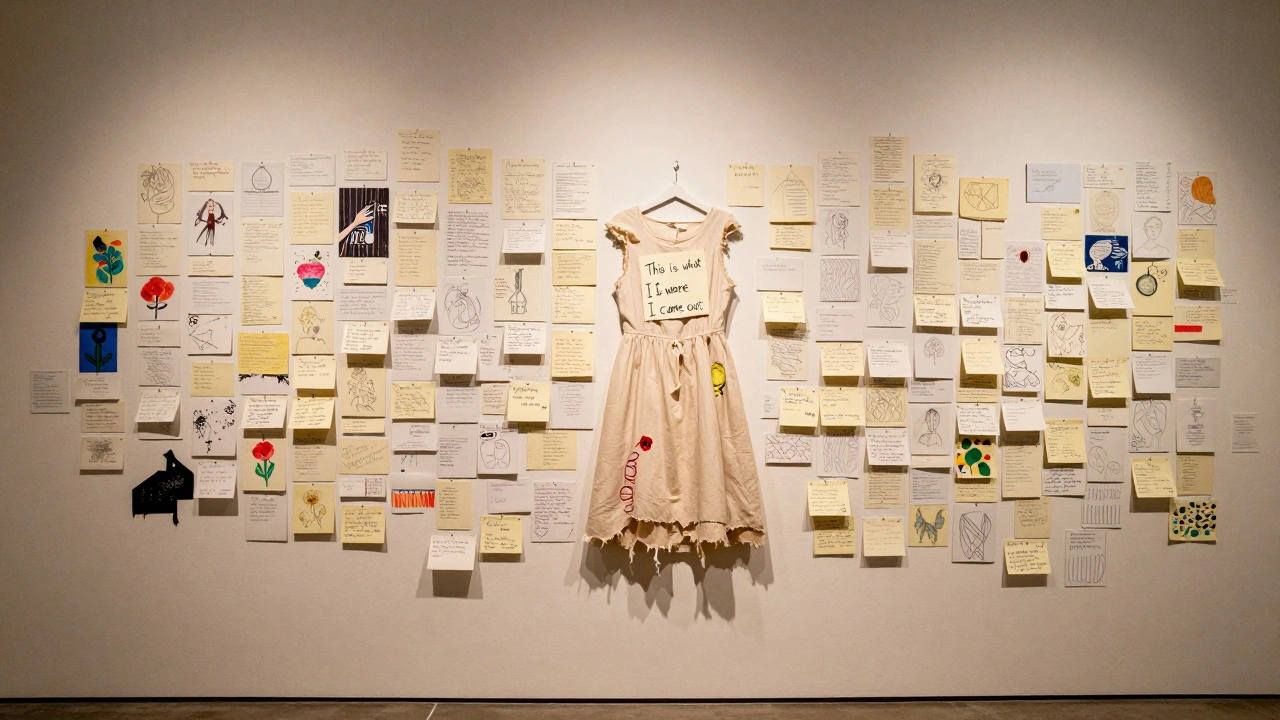

Many institutions still treat participation as a gimmick. “Let’s add a coloring wall!” But true participatory exhibitions don’t just invite input-they give up control.At the Portland Art Museum in late 2024, curator Elena Ruiz opened a room with 300 empty frames. Visitors were invited to hang their own art. Not reproductions. Not selfies. Original work-drawings, poems, torn fabric, handwritten letters. No theme. No jury. No labels. Just the walls, the frames, and the people.

By the end of the month, over 1,200 pieces had been added. A teenager hung a poem about her grandmother’s funeral. A retired teacher left a watercolor of his first car. A nonbinary artist pinned a threadbare dress with a note: “This is what I wore when I came out.”

The museum didn’t curate the show. The community did. And when visitors returned weeks later, they weren’t just looking at art. They were looking at themselves.

This model challenges the idea that curators are gatekeepers. What if the gatekeeper is everyone? What if the authority of the museum isn’t in its collection-but in its willingness to let go?

Designing for Uncertainty

Creating an experimental exhibition isn’t like planning a traditional one. You can’t storyboard it. You can’t predict the outcome. You have to design for chaos.Here’s how it works in practice:

- Start with a question, not a theme. Instead of “The Future of Identity,” ask: “What would you leave behind if you disappeared tomorrow?”

- Build in failure. If a participant doesn’t engage, that’s not a problem-it’s data. The exhibition evolves based on what works and what doesn’t.

- Remove the barrier between artist and audience. If someone wants to add something, let them. If they want to remove something, let them.

- Accept that the show will change daily. A piece might be covered in paint one day, shredded the next. That’s not damage. That’s dialogue.

The most successful experimental exhibitions don’t have a final version. They have a trajectory. They’re alive.

Why This Matters Now

In a world saturated with digital content-endless scrolling, algorithm-driven feeds, passive consumption-physical spaces that demand presence feel revolutionary. People are tired of being spectators. They want to be part of something real.Studies from the University of Oregon’s Center for Cultural Engagement show that visitors to participatory exhibitions stay 3.7 times longer than those in traditional shows. They return more often. They talk about it. They bring friends. They write letters to the museum.

And it’s not just about attendance numbers. It’s about trust. When a museum lets you hang your letter on the wall, it’s saying: “Your voice matters here.” That’s a rare thing in institutions that have spent centuries deciding what’s valuable.

Experimental formats aren’t just trendy. They’re necessary. They’re how culture stays alive when so much of it is being digitized, commodified, and flattened.

What’s Next?

The next frontier? Exhibitions that don’t end when the gallery closes.Some curators are now designing “living exhibitions”-projects that continue in public spaces long after the formal run. A project in Berlin turned a museum’s participatory archive into a traveling bus that visits neighborhoods, letting people add to it on the spot. Another in Toronto turned a gallery into a community kitchen where meals were cooked from recipes submitted by visitors, then served weekly.

These aren’t extensions of the exhibition. They’re its natural evolution.

Soon, we may stop calling them “exhibitions” at all. Maybe they’ll just be called “gatherings.”

Are experimental exhibitions just for art lovers?

No. In fact, they’re designed for people who don’t usually visit museums. These formats remove the intimidation factor. You don’t need to know art history. You just need to show up. A single handwritten note, a moment of silence, a shared laugh-those are all valid contributions. The most powerful moments in these exhibitions often come from strangers who never thought they belonged there.

Can museums afford to let go of control like this?

It’s expensive-not in dollars, but in courage. Letting visitors change the show means accepting unpredictability. Some institutions fear vandalism, controversy, or loss of authority. But the real cost is in staying static. Audiences are leaving traditional spaces because they feel like bystanders. The museums that survive are the ones willing to risk control for deeper connection.

Do these exhibitions have any lasting impact?

Yes-but not in the way you might think. You won’t find them in permanent collections. Instead, they change people. A participant in a 2023 project in Detroit said, “I didn’t know I could make something that mattered until I saw my drawing on the wall.” That’s the legacy: not artifacts, but transformed perspectives. The exhibition fades, but the sense of agency stays.

Is participation just a way to boost visitor numbers?

Some institutions use it that way. But the best ones don’t. True participatory work doesn’t measure success by attendance. It measures it by vulnerability. Did someone share something they’ve never told anyone? Did someone leave feeling seen? Those are the metrics that matter-and they can’t be tracked on a spreadsheet.

What’s the difference between participatory art and interactive technology?

Interactive tech responds to inputs-touch, motion, voice. But it doesn’t change based on human meaning. Participatory art changes because of what people feel, believe, or carry with them. A screen might react to your hand movement. A participatory exhibition reacts to your grief, your joy, your silence. One is a machine. The other is a mirror.