Conservation Ethics: Why Minimal Intervention and Honesty Matter Most

When you walk into a museum and see a 2,000-year-old statue, perfectly restored, gleaming under the lights, do you ever wonder what was lost to make it look that way? Or worse-what was hidden? This isn’t just about cleaning dirt off ancient stone. It’s about conservation ethics: the quiet, powerful choices conservators make every day about what to fix, what to leave alone, and how honest they’re willing to be about what they’ve done.

What Does Minimal Intervention Really Mean?

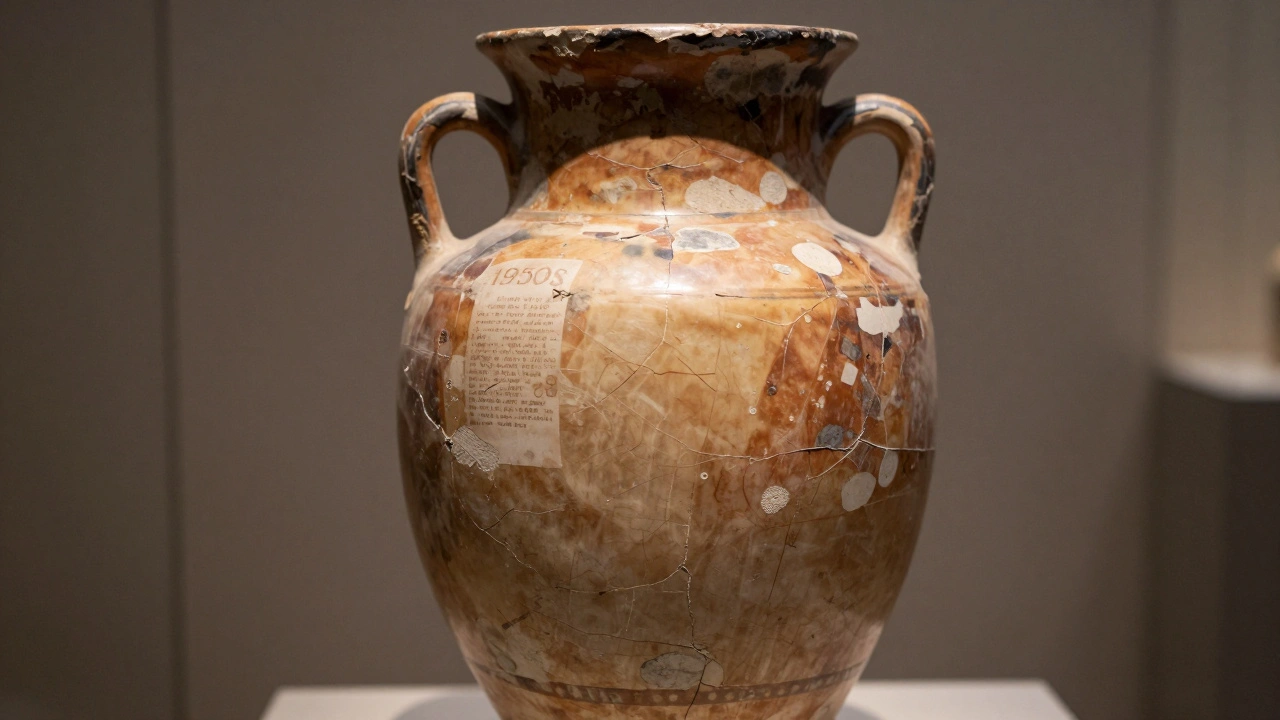

Minimal intervention isn’t about doing less because you’re lazy. It’s about respecting the object’s history. Every scratch, crack, or faded pigment tells a story. A Roman amphora with a missing handle isn’t broken-it’s a record of how it was handled, traded, buried, and dug up. When conservators glue on a brand-new handle made of modern resin, they’re not fixing it. They’re rewriting its history. In 2019, the Getty Museum faced this exact dilemma with a 4th-century BCE Greek vase. One fragment had been reassembled in the 1950s using plaster and paint to fill gaps. Later analysis showed the original glaze was still intact under the fill. Instead of removing the old restoration, they left it in place-clearly labeled. The vase now shows both its ancient form and the 20th-century attempt to ‘fix’ it. That’s minimal intervention in action: preserving layers of history instead of erasing them. The rule isn’t “do nothing.” It’s “do only what’s necessary to stop decay, not to make it look new.” That means stabilizing a flaking paint layer, not repainting it. Supporting a cracked wooden frame, not replacing the whole thing. Letting the patina of age stay where it belongs.Honesty Isn’t Optional-It’s the Foundation

Imagine you’re looking at a Renaissance painting. The sky is missing. The rest is pristine. You’re told it’s been restored. But you can’t tell where the original ends and the new paint begins. That’s not restoration. That’s forgery. Honesty in conservation means clearly marking what’s original and what’s added. It means using materials that can be removed later without harming the original. It means never trying to trick the viewer into thinking something is older or more complete than it is. In 2021, the National Gallery in London restored a 17th-century portrait. The original background had faded to a dull gray. Rather than repainting the sky, conservators used a reversible, transparent overlay that allowed visitors to see both the original surface and a digital reconstruction side by side. No guesswork. No deception. Just clarity. This isn’t just about aesthetics. It’s about trust. Once a conservator hides a repair, the entire object becomes suspect. If one thing was faked, what else was? Museums lose credibility. Collectors lose confidence. And the public loses the chance to understand what’s real.

When Is Intervention Necessary?

Minimal doesn’t mean passive. Some objects are falling apart. A 1,000-year-old manuscript is crumbling. A wooden sculpture is infested with beetles. If you do nothing, it’s gone forever. That’s when intervention is not just allowed-it’s required. The key is to intervene in the least invasive way possible. For the manuscript, that might mean humidifying the pages gently to re-adhere flaking ink, then storing them in a climate-controlled case. For the sculpture, it could mean injecting a non-toxic, reversible insecticide and reinforcing weak joints with a lightweight composite, not solid wood. Conservators use a simple checklist before touching anything:- Is the object at risk of immediate loss?

- Can we stabilize it without altering its appearance?

- Can the intervention be undone without damage?

- Will this change how future researchers understand the object?

The Hidden Cost of Over-Restoration

The worst damage to cultural heritage doesn’t come from neglect. It comes from well-meaning overzealousness. In the 1980s, a major European cathedral underwent a full restoration. Workers sandblasted centuries of soot off stone carvings, repainted faded frescoes with modern pigments, and replaced broken statues with exact copies. At the time, it was praised. Today, it’s a cautionary tale. Original carvings, worn by time and weather, held subtle details that told stories of medieval craftsmanship. The sandblasting erased them. The new paint didn’t match the original chemistry-it cracked within five years. The copies? Made with modern tools, they lacked the hand-carved imperfections that proved authenticity. That cathedral now spends more money maintaining its restoration than it ever did preserving the original. And researchers can’t study the real thing anymore-it’s gone. This isn’t rare. It happens in homes, churches, and public monuments every year. People think “restoration” means “make it look like new.” But conservation isn’t about beauty contests. It’s about truth.

What You Can Do-Even If You’re Not a Conservator

You don’t need a lab coat to support ethical conservation. If you own an old object-a family heirloom, a vintage poster, a worn-out book-you’re already part of this story. Here’s how to act ethically:- Don’t clean it with household products. Vinegar, bleach, or even a damp cloth can ruin finishes, inks, or metals.

- Take photos before touching anything. Document cracks, stains, and repairs. That’s your baseline.

- Consult a professional conservator-not a restorer or antique dealer. Look for membership in the American Institute for Conservation (AIC) or equivalent.

- Ask: “What’s the least I can do to keep this safe?” Not: “How can I make it look better?”

- If something is repaired, ask for documentation. Keep it with the object. Future owners deserve to know what’s real.

The Bigger Picture: Ethics Beyond Objects

Conservation ethics aren’t just about paint and plaster. They’re about how we value history itself. When we choose honesty and minimal intervention, we say: History is not a project to be completed. It’s a conversation to be respected. That means accepting that some things are incomplete. That some stories end in fragments. That beauty doesn’t require perfection. The most powerful conservation work isn’t the one that makes an object look brand new. It’s the one that lets you feel the weight of time-the cracks, the repairs, the quiet gaps where history was lost, and still, somehow, survives.What’s the difference between conservation and restoration?

Conservation focuses on preserving what’s original, stabilizing damage, and preventing further decay-with minimal changes. Restoration tries to return an object to how it looked at a specific point in time, often by replacing missing parts. Conservation respects the object’s entire history. Restoration often erases parts of it.

Can I restore an old family item myself?

It’s risky. DIY fixes-like gluing broken ceramics with super glue or repainting faded wood-often cause permanent damage. Materials you use at home aren’t reversible and can react badly with original materials. If it’s sentimental, get a professional conservator. They can stabilize it without altering its value or meaning.

Why not just replace a broken piece with a new one?

Because history isn’t just about function-it’s about authenticity. A new replacement, no matter how perfect, lacks the material evidence of the past. Original materials carry information: how they were made, where they came from, how they aged. Replacing them erases that data. Conservation keeps that evidence alive, even if the object is incomplete.

Do museums ever hide repairs?

Yes-and it’s a serious ethical violation. Reputable institutions now use reversible materials and clearly label repairs. Some even use digital overlays or lighting to show original vs. restored areas. Hiding repairs undermines trust and misleads researchers and the public. Ethical museums prioritize transparency over aesthetics.

Is minimal intervention expensive?

It can be, but not always. Minimal intervention often costs less in the long run because it avoids irreversible changes that require future corrections. The real cost isn’t money-it’s time. Waiting, monitoring, and researching take patience. But skipping those steps leads to far more expensive mistakes later.