Biennial Politics: How Curatorial Agendas Shape National Pavilions in Contemporary Art

Every two years, the Venice Biennale turns the city into a global stage for art, politics, and national identity. But behind the glossy brochures and Instagram-ready installations lies a quieter, more powerful force: curatorial agendas that don’t just select art-they redefine what a country stands for.

What Really Happens Inside a National Pavilion

When you walk into the U.S. Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, you’re not just seeing art. You’re seeing a carefully constructed narrative. The pavilion isn’t a neutral space. It’s a diplomatic tool, a cultural embassy, and sometimes, a propaganda machine. The curator doesn’t just pick artists. They choose which stories get told, which voices are amplified, and which histories are left out.

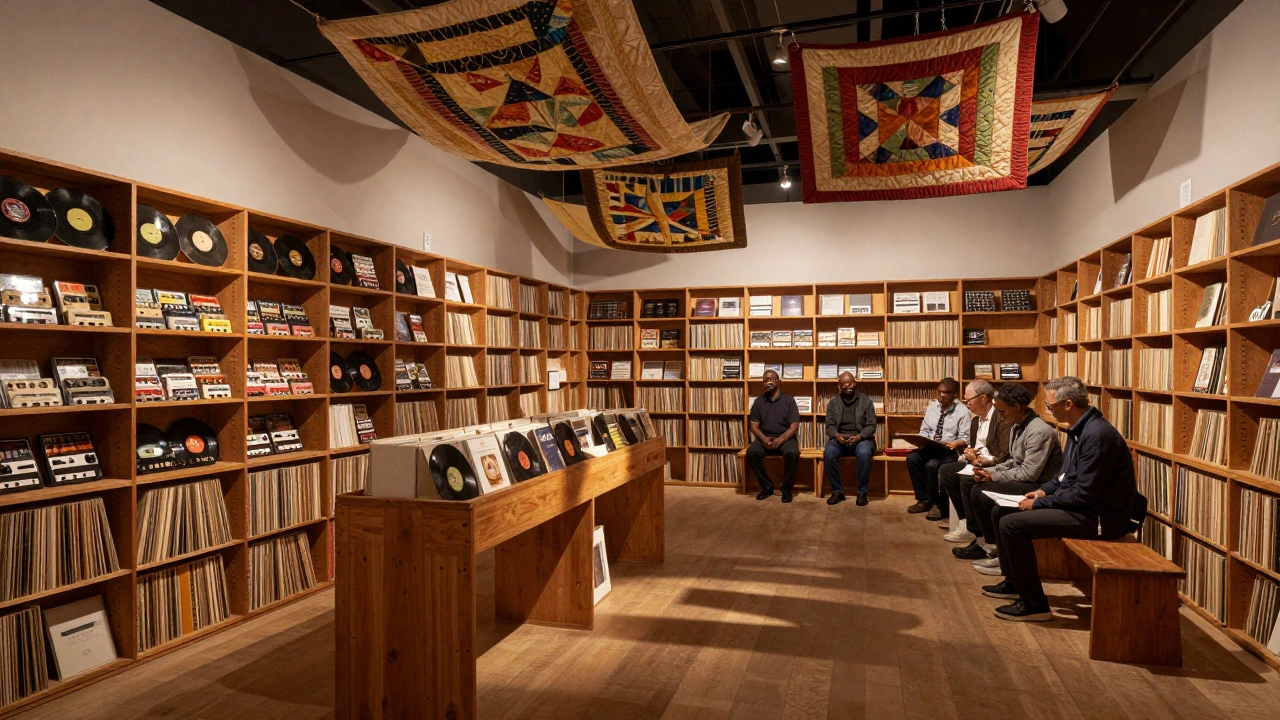

Take the 2022 U.S. Pavilion, curated by Theaster Gates. Instead of showing flashy, market-ready works, he turned the space into a living archive of Black American spirituals, community gatherings, and archival materials from Chicago’s South Side. It wasn’t about aesthetics alone. It was about reclaiming cultural memory. That choice didn’t happen by accident. It was a deliberate political act-one that challenged the U.S. government’s usual image of itself on the world stage.

Compare that to Italy’s 2024 pavilion, where curators leaned into Renaissance aesthetics, using gold leaf and classical sculpture to reinforce a narrative of timeless artistic superiority. No controversy. No discomfort. Just tradition, polished and presented. The message? Italy’s cultural power hasn’t faded-it’s eternal.

Who Gets to Speak for a Nation?

Who selects the curator? Usually, it’s a government ministry, a national arts council, or a private donor with political ties. In countries like China or Russia, the state directly appoints curators. In others, like Germany or Canada, there’s more room for independent voices-but even there, funding comes with strings.

South Korea’s 2023 pavilion featured a video installation about the comfort women, a painful chapter of its wartime history. The government approved it. Why? Because the international art world was watching. The pavilion became a tool for soft diplomacy, turning historical trauma into a global conversation. It wasn’t just art. It was a statement: we are not afraid to face our past.

Meanwhile, smaller nations-like the Philippines or Senegal-often struggle to get funding. Their pavilions rely on private sponsors or diaspora networks. That means their curatorial agendas are shaped less by national policy and more by who’s willing to pay. The result? A fragmented, uneven representation of global culture.

The Hidden Rules of Biennial Selection

There are no official guidelines for what makes a good national pavilion. But there are unwritten rules. Curators know that:

- Art that’s too political gets rejected by conservative governments.

- Art that’s too abstract gets ignored by the public.

- Art that’s too local doesn’t travel well internationally.

- Art that’s too critical of the state risks losing funding.

So curators walk a tightrope. They need to satisfy their sponsors, appeal to international audiences, and still say something meaningful. That’s why you see so many pavilions that feel polished, safe, and strangely empty. They’re designed to be understood by diplomats, not challenged by critics.

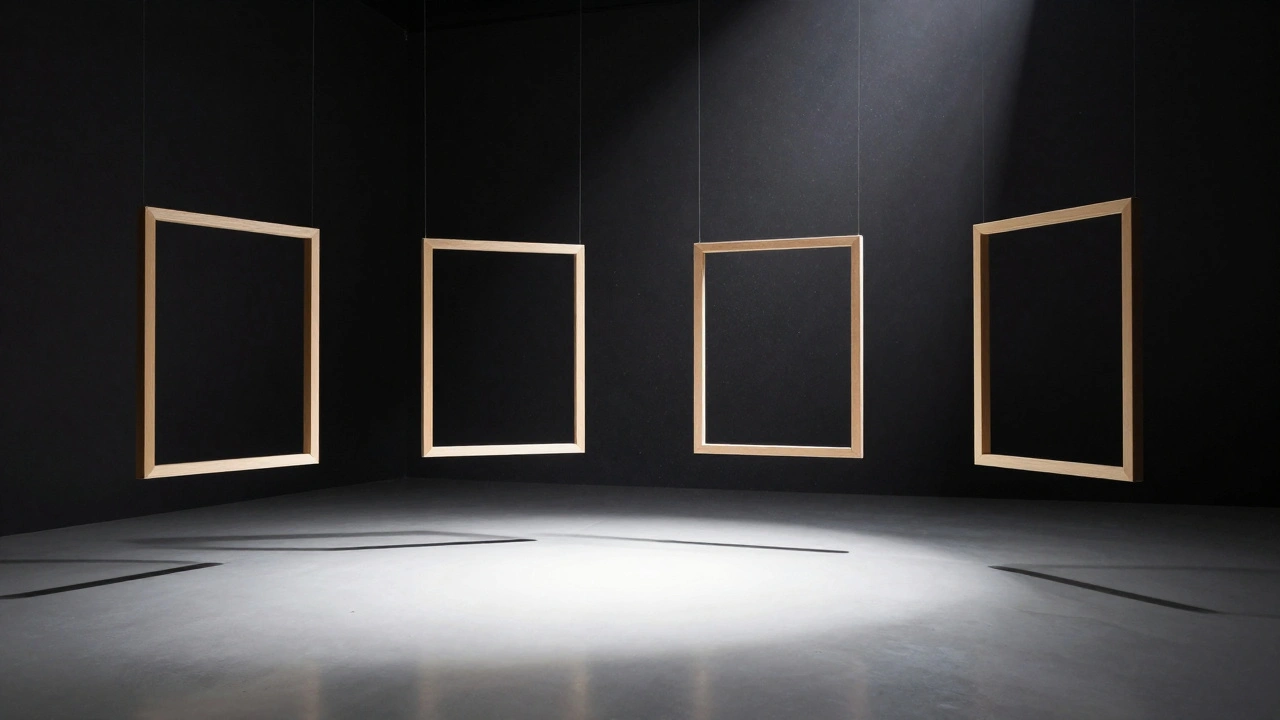

But some curators break the mold. In 2017, the Zimbabwean pavilion, curated by Tendai J. Chirinos, featured nothing but empty frames. No paintings. No sculptures. Just the idea of absence. The message? Our artists are not allowed to leave. Our stories are censored. Our voices are silenced. It was quiet. It was powerful. And it made headlines.

Why Venice Still Matters

Some say the Venice Biennale is outdated. That it’s a relic of colonial power structures, where Western nations dominate the conversation. And they’re right-sort of. The pavilion system still favors countries with deep pockets. But it’s also one of the few places where a small nation can punch above its weight.

Look at the 2024 pavilion from Timor-Leste. A country with a population of 1.3 million and no major art institutions. They sent a single artist, a woman named Ana Bela, who wove together oral histories of resistance from her grandmother’s village into a massive textile installation. No government funding. No corporate sponsors. Just community, memory, and a lot of handmade thread.

It didn’t win awards. But it stayed with people. Why? Because it didn’t try to be grand. It was honest. And in a space full of spectacle, honesty became revolutionary.

The Future of National Pavilions

The next decade will change how pavilions work. Climate change is forcing countries to rethink their carbon footprints. Flying in tons of artwork? That’s becoming harder to justify. Some pavilions are shifting to digital-only presentations. Others are using local materials, building installations on-site to reduce shipping.

And then there’s the rise of non-state curators. Indigenous collectives. Refugee artists. Community networks. They’re not waiting for government approval. They’re creating their own pavilions-in abandoned warehouses, online platforms, or even in the streets of Venice.

The Venice Biennale may still be the most visible stage, but it’s no longer the only one. The real power is shifting-from institutions to communities, from state agendas to grassroots voices.

What does that mean for you? If you’re looking at a national pavilion, don’t just ask: What’s the art? Ask: Who decided this was the story worth telling? And more importantly: Who’s still not in the room?

What is the Venice Biennale?

The Venice Biennale is a major international arts festival held every two years in Venice, Italy. It began in 1895 and features national pavilions, exhibitions, and curated shows across visual art, architecture, dance, music, and theater. The art portion is the most famous, with over 90 countries participating. Each nation selects its own curator and artists to represent its cultural identity.

Why do countries invest so much in their pavilions?

Countries invest in pavilions because they’re a form of soft power. A well-curated pavilion can shift global perceptions, promote cultural diplomacy, and even influence tourism and trade. For some, it’s about reclaiming history. For others, it’s about projecting modernity. Governments fund pavilions because they see them as extensions of foreign policy-art as diplomacy.

Can a pavilion be too political?

Yes. Many national pavilions are censored or altered before opening. Governments have fired curators, removed artworks, or even pulled out of the Biennale entirely when the content challenged national narratives. In 2019, Saudi Arabia’s pavilion was quietly toned down after initial plans included critical commentary on gender laws. The line between art and politics is thin-and governments often try to erase it.

Are there alternatives to the national pavilion model?

Absolutely. Groups like the Collective for Independent Art and Artists Without Borders now organize parallel exhibitions during the Biennale. These spaces feature artists from nations with no pavilion, or those excluded by their governments. Some are digital. Others are pop-up installations in abandoned buildings. They’re not funded by states-but they’re often more honest.

How do curators choose artists for a pavilion?

Curators usually start with a theme-like "memory," "migration," or "decolonization." Then they look for artists whose work aligns with that theme, often traveling to studios, attending graduate shows, or reading academic journals. They avoid artists who are already famous in the commercial art world, preferring those with deep local roots. The goal isn’t to sell art-it’s to tell a story that reflects a nation’s identity, real or imagined.