Art Forgery Red Flags: Common Forger Mistakes That Experts Spot Instantly

Every year, museums, galleries, and private collectors lose millions to art forgeries. Some fakes are so good they fool experts for decades. But here’s the truth: no forger gets it right every time. Even the most skilled forgers leave behind clues-tiny mistakes that scream "fake" to anyone who knows where to look.

They Use Modern Materials in Old Paintings

One of the biggest red flags? Modern pigments in supposedly centuries-old artwork. Take titanium white. It wasn’t commercially available until the 1920s. If a painting claimed to be from 1780 has titanium white in its whites, it’s not from 1780. It’s from the 20th century or later. Same goes for phthalocyanine blue-a synthetic pigment invented in 1935. You’ll find it in fake Old Masters all the time.

Even canvas tells a story. Linen from the 1600s has a different weave density than modern linen. Carbon dating the canvas helps, but so does simple microscopy. Forgers often buy modern linen, stretch it tight, and distress it with sandpaper to make it look old. But under UV light, the surface glows unevenly. The varnish and paint layers don’t age the same way.

They Copy the Style, But Miss the Hand

Forgers don’t just copy a painting-they copy the subject. But style isn’t just about brushstrokes. It’s about rhythm. A real artist doesn’t paint every detail the same way. Rembrandt’s brushwork has a kind of hesitation, a push and pull. His underpainting shows through in places, like he was thinking as he painted. Forgers try to replicate that, but they overdo it. Their brushstrokes are too consistent, too perfect. It looks rehearsed, not spontaneous.

Look at the signature. Many forgers put the artist’s name in the wrong place. Van Gogh signed his paintings in the lower right corner, usually with a firm, upward stroke. A fake might put it too high, or use a thinner line. Even the ink matters. Iron gall ink used in the 1800s darkens over time. Modern ink stays flat. Under magnification, the difference is obvious.

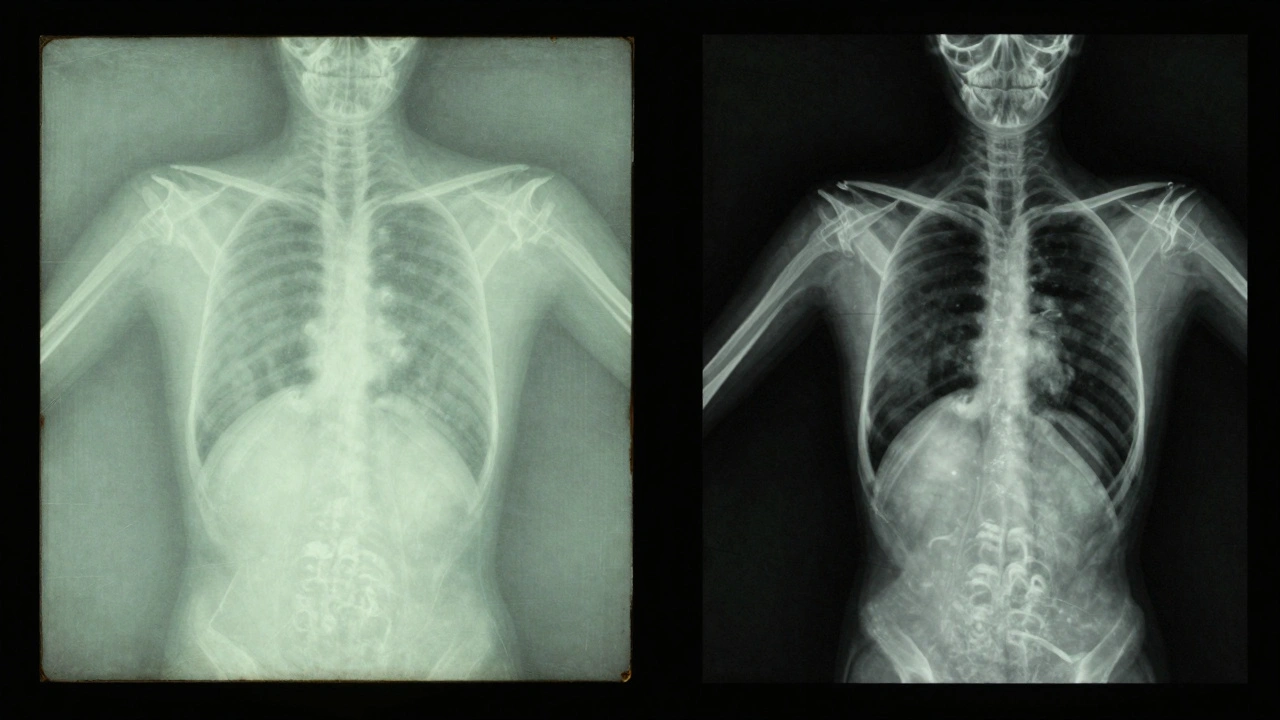

The X-Ray Doesn’t Lie

Here’s where most forgers collapse. They don’t realize that paintings have layers beneath the surface. X-ray imaging reveals underdrawings, changes, and even earlier paintings hidden underneath. Authentic works often show pentimenti-where the artist changed their mind. A figure’s hand moved, a landscape shifted. These are signs of a living process.

Fakes? They usually have none. Some forgers paint over a blank canvas. Others copy from a photograph, so there’s no history of revision. When an X-ray shows a perfectly clean underlayer, that’s a warning. One famous forgery, sold as a lost Caravaggio, had no underdrawing at all. Caravaggio didn’t sketch-he painted directly onto the canvas. No sketch? No Caravaggio.

Provenance That Doesn’t Add Up

Provenance-the paper trail of ownership-is supposed to be the anchor of authenticity. But forgers create fake receipts, forged letters, and invented galleries. A painting might come with a 1940s auction catalog, but the auction house didn’t exist until 1952. Or the signature on the back matches a dealer who died in 1923… but the painting was supposedly sold in 1935.

Even the paper matters. Old auction catalogs were printed on rag paper, not wood pulp. Modern paper yellows differently under UV light. A fake certificate might look old, but the font doesn’t match any printer from that era. Experts cross-reference archives. If the provenance doesn’t fit the timeline, it’s a lie.

They Ignore the Chemical Signature

Every artist used specific materials. Vermeer used lapis lazuli for blue, ground from Afghan stones. It was expensive. A fake Vermeer might use cheaper azurite. Under a spectrometer, the chemical signature is different. Even the oil used matters. Linseed oil from the 17th century had different fatty acid ratios than modern oil. It oxidizes differently over time.

Some forgers try to age paint with heat or chemicals. But that creates unnatural cracking patterns. Real craquelure forms over centuries in a slow, branching pattern. Fake craquelure looks like cracks in dried mud-random, jagged, and too uniform. It’s the kind of thing you’d see in a museum exhibit labeled "modern imitation."

The Color Doesn’t Age Right

Color shifts over time. Lead white darkens. Vermilion turns dull. But forgers don’t understand this. They paint the colors as they see them in a photo-bright, saturated, untouched by time. A real Rembrandt portrait might have a face that’s lost its pink tones, now a soft gray. A fake? The cheeks are still rosy, like it was painted yesterday.

Even the varnish layer tells a story. Old varnish yellows and thickens. Modern varnish stays clear. UV light reveals whether the varnish is original or a recent coat. If the varnish covers the entire painting evenly, without any wear around the edges, it’s a sign it was applied later. Original varnish shows wear from handling, cleaning, and time.

They Forget the Context

Art doesn’t exist in a vacuum. A fake might show a woman wearing a dress from 1810 in a painting claimed to be from 1750. Or a landscape includes a building that wasn’t built until 1820. Forgers research the artist’s style but skip the historical context. They don’t know what people wore, what tools were used, or what the world looked like at the time.

One forgery showed a horse with a saddle from the 1890s in a painting supposedly from 1730. The artist who made it didn’t realize saddles changed dramatically between centuries. Experts caught it because they knew the evolution of equestrian gear. That’s the kind of detail you only learn by studying archives-not by copying a photo.

How to Protect Yourself

If you’re buying art, don’t rely on a seller’s word. Ask for:

- Scientific testing reports (X-ray, infrared, pigment analysis)

- Provenance documents with verifiable sources

- Authentication from a recognized expert or institution

- Access to the painting’s history through museum archives

Reputable dealers don’t mind if you hire an independent conservator. In fact, they expect it. If they refuse, that’s a red flag bigger than any brushstroke.

And remember: if it seems too good to be true, it is. A "lost" Picasso at half the auction price? A "previously unknown" Monet in a garage sale? Those aren’t discoveries-they’re traps.

Can a forgery ever be detected without scientific tools?

Yes, but only if you know what to look for. Experts can spot inconsistencies in brushwork, signature placement, or historical inaccuracies just by studying the painting closely. For example, a fake might show clothing or objects that didn’t exist in the claimed time period. But scientific tools like X-ray, UV, and pigment analysis are the only way to be certain. Human eyes are good, but machines don’t lie.

Are all old paintings with craquelure authentic?

No. Craquelure-the network of fine cracks in paint-is often copied by forgers. But real craquelure forms slowly over decades, shaped by humidity, temperature, and how the canvas was stretched. Fake craquelure is often painted on or forced with heat, making it too uniform or too deep. Real cracks branch like tree roots. Fake cracks look like scratches or cracks in dried clay.

Do museums still get fooled by forgeries?

Yes. Even top museums have been fooled. In the 1990s, the Getty Museum bought a forged Greek statue that passed all tests at the time. Later, pigment analysis revealed modern materials. The point isn’t that experts are careless-it’s that forgers get better every year. That’s why museums now use multiple methods: chemistry, history, provenance, and technology. No single test is foolproof.

What’s the most common type of art forgery today?

Modern and contemporary art fakes are the most common. Artists like Picasso, Warhol, and Pollock are targeted because their works are valuable and often signed. Forgers use original canvases, fake signatures, and even fake certificates. Some are even sold through fake galleries with fabricated auction records. The lack of clear documentation for modern art makes it easier to fake.

Can a painting be partially fake?

Absolutely. Many forgeries aren’t fully fake-they’re altered originals. A real 18th-century landscape might have a signature added by a forger to make it look like a famous artist. Or a damaged section might be repainted with modern paint. These are called "enhanced" fakes. They’re harder to detect because part of the work is authentic. But scientific analysis usually reveals the mismatch in materials or technique.